|

A day off work while in Massachusetts gave us an opportunity to travel into Boston for a day of exploring. We gathered with friends at a commuter train station in Fitchburg and boarded for a 1.5-hour journey into the city. After deboarding, we went underground to catch a subway that would take us close to the start of Boston’s Freedom Trail at Boston Common. The 2.5-mile, red-brick trail meanders through the city, with stops and plaques at important places in history along the way. Here are some of our highlights. Historical Landmarks Erected in 1897, a bronze, sculpted memorial pays tribute to Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment, the first all-Black volunteer unit in the Civil War. (Think “Glory,” the movie that tells the story.) Although most of the regiment lost their lives in the attack of Fort Wagner in South Carolina in 1863, they changed the tide of American sentiment regarding Black soldiers. Across the street from the memorial stands the Massachusetts State House. The gold-domed building is open for free guided tours. We didn’t plan ahead, unaware we needed to schedule a tour. From there, we navigated past the Park Street Church (think “National Treasure”), King’s Chapel, the Boston Latin School, the Old South Meeting House, and two cemeteries in which key historical figures are buried: Benjamin Franklin, Paul Revere, and John Hancock, just to name a few. Opting to save our funds for melting pot food, we bypassed going inside King’s Chapel and the Old South Meeting House, both of which required payment for entry. Ready for a rest and a bite to eat, we stopped at Faneuil Hall, the home of America’s first town meeting. Directly behind it is Quincy Market, which hosts stalls peddling all kinds of food. We settled in at an outdoor Irish eatery that could seat our group. Our niece, Sarah, who lives in Boston and just graduated from nursing school, joined us for lunch. We munched on chicken and fish sandwiches, French onion soup, southwestern salads, and other delectable delights. Water Views and Italian Desserts Refreshed and refueled, we took a brief detour to explore beautiful Boston Harbor and its wharfs before rejoining the trail. It took us to Paul Revere’s house (another fee-for-entry point) and the Old North Church, the start of Paul Revere’s midnight ride to announce that the British were coming. Wanting to sample some sweet treats while in the area, we veered off the trail and into the North End, known for its authentic Italian dishes, pastries, and coffees. Mike’s Pastry is where most visitors go. Sarah gave us the inside scoop and directed us to where the locals go: Bova’s Bakery. Pastries of all kinds and colors filled the glass showcase: cheesecakes, cannolis, lobster tails, cakes, cookies, chocolate-covered strawberries, and more. I chose tiramisu, and Bob selected Boston cream cake. Our friends got their goods, and we headed back to the tree-shrouded courtyard between Paul Revere’s midnight ride statue and the Old North Church to enjoy our delicacies. Relaxation on the Wharf Electing to save a mile of walking by skipping visits to the USS Constitution and the Bunker Hill Monument, both of which we’ve seen before, we headed back toward Quincy Market. Bob and Sarah made a stop at the Union Oyster House for some fresh raw seafood. The rest of us moseyed on to Faneuil Hall, where we decided we had had enough walking for one day. After Bob and Sarah caught up, we ambled back to the wharf to a place called Joe’s for rest and refreshment. Seated with an expansive view of the water, we shared appetizers of buffalo chicken tenders, spinach and artichoke dip, nachos, and candied brussels sprouts. Satisfied with a good day in Boston, we navigated to a T subway station, stopping to pick up coffee at Dunkin’ on the way. Dunkin’ got its start south of Boston in Quincy in 1950. We said goodbye to Sarah and descended to catch a subway that would take us to Union Station, where we boarded a train back to Fitchburg. You might also like Our Life on the Mighty Mississippi.

2 Comments

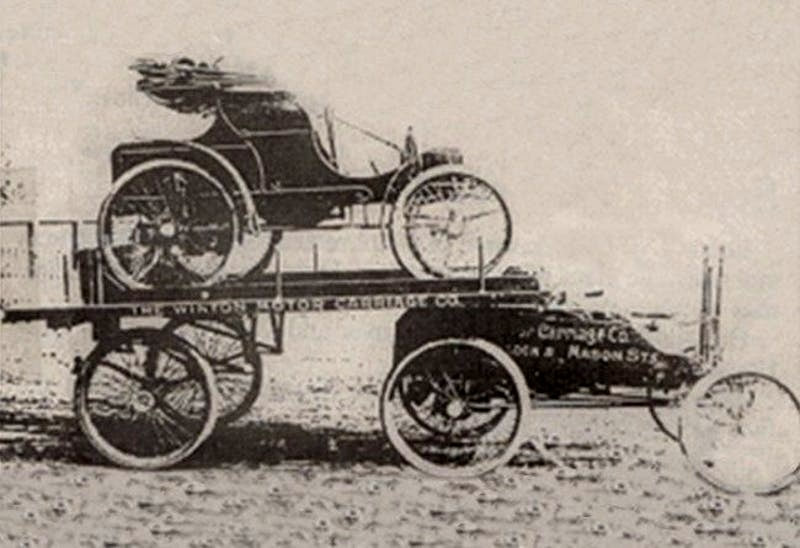

Living in a fifth wheel has its pluses and minuses. If we could change anything about it, we’d make it shorter. Our 13-foot, 3-inch height makes it tricky to navigate a lot of areas, including state campgrounds. We always have to be on alert for low-hanging branches and low-clearance bridges. The Northeast U.S. is notorious for low-clearance bridges. When its towns and cities were established in the 1600s, most people got around on foot. If they had to travel great distances, they would take a stagecoach. Although New York’s first bridge emerged in 1693 to connect Manhattan and the Bronx, most bridges didn’t appear until the 1800s. At that time, tall vehicles didn’t exist. Early Semi-Trucks The first semi-truck came on the scene in 1898. Alexander Winton designed it specifically to deliver a car on a trailer to its buyer somewhere in the country. This eliminated wear and tear on the vehicle from driving it to its purchaser. In 1914, August Charles Fruehauf invented a more substantial semi-trailer to transport his boat. It was later adapted to move lumber. As automobiles became more popular, car dealers needed more efficient ways to deliver the vehicles to purchasers. So, in the 1930s, George Cassens crafted a trailer that could carry four cars at a time. Between 1929 and 1944, Mack Trucks entered the market, creating 2,601 semi trailers. Peterbilt trucks followed in 1939 to transport logs. These early semis paled in comparison to today’s mammoth 18-wheelers that stand 13 feet, 5 inches tall. It wasn’t until 1983 that trailers stretched as long as 48 feet, only 7 feet shy of today’s standard 53 feet. Increasing RV Heights Early campers weren’t much taller than the trucks pulling them. Even initial fifth-wheel campers averaged 8 to 8.5 feet tall. Many original models required people to crawl up to the bed over the top of the truck bed. Gradually, fifth wheels increased in height to about 10 feet, making them easier to live in for a weekend or vacation getaway. RV manufacturers started installing slideouts in fifth wheels in the 1990s to create more living space. Providing adequate ceiling height in these slideouts meant the supporting rig around the slideouts had to be taller. The average height of a modern fifth wheel RV is 13 feet, with many as tall as 13 feet, 5 or 6 inches. Today, towering RVs and semi-trucks roam the highways. Although the width of these vehicles is limited to 102 inches (8 feet, 6 inches) in the U.S., according to the U.S. Department of Transportation, there’s no nationwide vehicle height limit. That varies per state, typically between 13 feet, 6 inches and 14 feet. Maneuvering Roadways In New York City, arched bridges force high-clearance vehicles to drive in the middle lane to ensure they can clear. They’re prevented from certain roadways, where clearance is too low for safe passage. New York also lists clearances as 6 to 12 inches lower than the height of vehicles that can clear safely — unless the bridge says ACTUAL CLEARANCE. We found this out when we approached a bridge labeled 12’-11” and watched a standard semi pass through unharmed. We followed suit. Rumor has it this height discrepancy is to allow for safe passage even when roads are packed with snow. Low-clearance challenges aren’t limited to New York. They span all of New England too. Athol, Massachusetts, for example, has an overpass that’s only safe for vehicles 12-foot, 7 inches or less to maneuver. For some reason, a semi-truck driver tried to take the route. Maybe he thought the actual clearance was 13 feet, 7 inches, like in New York. His trailer hit hard, denting the top, and creating a loud boom. Ensuring Safe Passage

Most road atlases don’t display bridge and tunnel clearances. Similarly, although Google Maps does a good job showing us the quickest, most direct route between two points, it doesn’t take into consideration the height and length of our vehicle. Because of that, we can’t always trust that Google will navigate us safely, as the trucker in Athol discovered. For better results, we use an app called CoPilot. Its $30 annual fee is well worth the peace of mind it provides. We’re able to enter our vehicle dimensions and select if we want to use toll roads, ferries, propane-restricted routes, and more. Based on our choices, the app directs us safely to any destination we enter. Only one time we questioned the route CoPilot directed us to after a white-knuckled drive through winding roads in northeastern Tennessee. Other than that, we’ve fared well. We also make a point to look at the satellite view on Google Maps of any destination we choose and the path to get there to ensure it’s navigable for a rig our size. You might also enjoy Answers to Your Questions About Our RV Lifestyle. After an eventful time in Virginia Beach, Virginia, we wanted to venture to Ocean City, Maryland, to visit some friends we had made on our 2022 transatlantic cruise. Crossing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel offered the quickest, most direct route, saving 95 miles and about three hours of travel time through the congested Washington, D.C., area. Considered one of the seven engineering wonders of the modern world, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel is a 17.6-mile crossing of the Chesapeake Bay. Since opening in 1964, it’s taken more than 140 million vehicles from Virginia Beach to the state’s Delmarva Peninsula, or vice versa, traversing both over and under the water. The bridge-tunnel includes not one, but two tunnels, each about a mile long. Crossing the bridge-tunnel takes only about a half hour but can be nerve-racking in an RV if you’re unprepared for it. To Cross or Not to Cross? As the time approached for us to travel to Ocean City, Bob put his excellent research skills to use to explore our options to get there. The bridge-tunnel’s direct route and time savings made us give it serious consideration. Had other RVs made it through? Did semi-trucks use the route? How tight were the travel lanes? We had read that the max vehicle height for the tunnels is 13 feet, 6 inches, the size of semis. Our rig is 3 inches shorter, so we took some comfort in that, knowing we had a little more clearance than trucks did. Because of the potential stress of driving an RV across the bridge-tunnel, Bob had decided we’d forgo it and take the long, inland route instead. But advice from a friend made him reconsider. Jim had traveled the bridge-tunnel numerous times and had seen semis and RVs make it through with no issues. The only potential risk was weather. If conditions are too windy, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission closes the bridge-tunnel until conditions improve. We decided to keep our trip short and take the direct route across the bridge-tunnel. Travel Day The weather looked good on our day of departure. We waited to leave our campsite at First Landing State Park until about 9 a.m. to let traffic die down. Navigating to the bridge-tunnel proved easy enough. We made it to the toll plaza with no problems. Because we have E-ZPass, a transponder in Gulliver that electronically pays tolls we encounter, we didn’t have to exchange any funds. The toll worker asked if our propane was off. We assured her it was, and we were on our way, starting across the bridge. A semi-truck passed us, relaxing any remaining frayed nerves. Prior to this experience, we had thought the dimensions listed before tunnels and overpasses — 13’ 6” max height, in this case — were the measured distance from road to overpass/tunnel bottom. We learned those signs actually mean the listed dimensions are the maximum height for a vehicle to safely pass without hitting the bridge/tunnel. As we approached the first of the two tunnels, Thimble Shoal Channel Tunnel, and two-way traffic, Bob concentrated on keeping Gulliver and Tagalong in the middle of our lane. Clearance under the tunnel was fine. We had no problems, although we still got excited when we could see the light at the end of the tunnel. We emerged onto another bridge that led us to the second tunnel, the Chesapeake Channel Tunnel. As we approached that one, a semi-truck came out toward us, clearly demonstrating plenty of clearance. After that tunnel, we crossed another bridge before finally returning to land. Thankful for an uneventful experience, we pulled into the Eastern Shore of Virginia Welcome Center. There, we turned our propane back on to keep the food in our fridge and freezer cold as we journeyed to our destination in Ocean City.

You might also enjoy Starlink for RVs: An Upgraded Internet Experience. The state of Virginia has a lot to offer visitors. From history to beaches to natural attractions (think caverns and a bridge) and more, you’ll find something for everyone. What we enjoyed most was exploring the state’s vast history, thanks to our friends, Jim and Jenny, treating us to an amazing tour. Here are seven highlights, in no particular order: 1. George Washington’s Mount Vernon Spanning 500 acres today, Mount Vernon pales in comparison to its expansive 8,000 acres when the first U.S. president lived on the 18th-century plantation. The estate maintains a colonial feel, with workers dressed in period costumes to tell visitors about life in the 18th century. A walking tour will take you through stables, a blacksmith shop, gardens, the mansion, the distillery and gristmill, and even down to the wharf on the Potomac River. You can sit on a rocking chair on the mansion’s back porch and enjoy the view. Two museums on the property provide more details about the colonial days and estate. 2. Smithfield Ever heard of Virginia ham? What designates a ham with the Virginia label is the curing process: cured with salt, then smoked and hung to age in a smokehouse. The town of Smithfield, established in 1752, started its own Virginia ham business early on, thanks to the vision of Mallory Todd. Today, Smithfield houses the headquarters of Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest producer of pork, with locations in 29 states, as well as Europe and Mexico. Pork may be the staple of the town of Smithfield, but that’s not what draws visitors there today. Fifteen 18th-century houses and boutique shops line its main streets, offering a walking tour through history. You can even eat at a soda fountain and go inside a replica of the 1752 courthouse. And, for the small fee of $2 per person, you can see the world’s oldest ham and oldest peanut at the Isle of Wight County Museum. 3. First Landing State Park The first English settlers arrived on the shores of Virginia in 1607 at Cape Henry, right around the corner from First Landing State Park in Virginia Beach. The park spans 2,888 acres, offering 20 miles of trails, more than 200 campsites, 20 rustic cabins, four yurts, and 1.5 miles of Chesapeake Bay beach. The campground pays homage to the first landing with a historical exhibit in the office. Camping here served as a jumping-off point for us to investigate other historical attractions in the area. It also provided ample opportunities to walk to the beach on a whim and take in sunsets. 4. Jamestown Island After exploring the coastal areas of Virginia, the 104 English men and boys who landed at Cape Henry decided to make Jamestown their permanent home. The Jamestown Settlement, a living-history museum, lures visitors to relive life in the first English colony. If you want a more authentic experience, don’t stop at the Jamestown Settlement. Keep driving to Jamestown Island and visit Jamestown Rediscovery, where archaeologists are at work unearthing the historical Jamestown Fort. You can see the foundations for yourself and a replica of the Memorial Church, built to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the settlement. A tour through the Archaearium Museum gets you up close to artifacts the settlers used and provides insights into what life was like during the “Starving Time,” when two of every three Jamestown colonists died. 5. Colonial Parkway/Yorktown Battlefield After exploring Jamestown Island, you can enjoy a scenic, relaxing drive on the Colonial Parkway, which will take you from Jamestown to Yorktown. The 23-mile drive navigates through tree-covered roads, with historical stops along the way, including colonial Williamsburg. We didn’t stop there, opting to keep going to Yorktown. There, a driving tour meanders through the Yorktown Battlefield and the allied encampment, with placards detailing historical facts along the way. 6. USS Wisconsin Battleship With its location on the water, Norfolk has a long military history, dating back to 1917, when the U.S. entered WWI. The Naval Operating Base of yesteryear is now Naval Station Norfolk, the world’s largest naval station, supporting 75 ships and 134 aircraft. As a government employee, our host, Jim, was able to get us onto the naval base for a closer view of the amazing watercraft and aircraft our military uses. We saw carriers, supply ships, helicopters, airplanes, and much more. If you’re not able to get onto the base — and even if you are — visit the static display of USS Wisconsin, one of the Navy’s largest and last battleships built. You can take a self-guided tour to explore its decks. For a guided tour, $20 per person will get you either the engine room tour or the command and control tour. 7. Military Aviation Museum Because of our affiliation with the Commemorative Air Force, we’re drawn to aviation museums. The Military Aviation Museum in Virginia Beach did not disappoint. It offers a hangar dedicated to WWI planes and another two to showcase WWII planes, separated by Army and Navy.

The extensive collection of airplanes that still fly, landing on a grass strip, includes a B-25, “Wild Cargo,” named for her civil duty of transporting snakes and alligators after the war. Another notable warbird is the PBY Catalina, a mammoth flying boat. The collection spans fighters, bombers, trainers, liaisons, and more. And, you can take a guided tour of the Goxhill Tower, the authentic British “Watch Office” transferred from Europe to Virginia brick by brick and put back together. You might also enjoy A Historical Stop. |

AuthorThis is the travel blog of full-time RVers Bob and Lana Gates and our truck, Gulliver, and fifth wheel, Tagalong. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed